Looking for the teardown or how well the Kentli PH5 battery performs under load? Click the links to learn more.

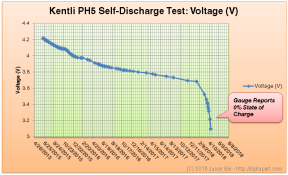

It’s finally happened – the self-discharge test of the Kentli PH5 Li-ion AA battery has finally come to an end… and it only took almost 3 years!

Kentli PH5 self-discharge test statistics

Self-Discharge Rate

I never anticipated this test would run for so long; although the PH5 did not have a manufacturer-specified self-discharge rate, marketing materials suggested that the batteries had a storage life that was “3-5 times longer than Ni-MH batteries”. Wikipedia states that after one year, normal Ni-MH batteries lose about 50% of their capacity, and low-self-discharge (LSD) Ni-MH batteries lose 15-30%.

Correlating this with the data collected from the Texas Instruments bq27621-G1 fuel gauge, the battery lost 40% of its charge within one year, placing it in between the standard and LSD Ni-MH chemistries. Using Excel’s SLOPE() function, the self-discharge rate was calculated to be 0.10108%/day.

Experimental Improvements

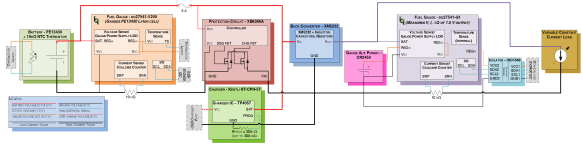

There is some error in State of Charge measurement when using the bq27621 fuel gauge. As it uses the Impedance Track algorithm, open-circuit voltage is used to determine a battery’s state of charge upon gauge initialization. This OCV curve is chemistry-specific, with slightly different formulations requiring different chemistry ID codes. The bq27621 has a fixed Chemistry ID of 0x1202 (LiCoO2/LCO cathode, carbon anode), but experimental data revealed a better-matched Chemistry ID of 0x3107, 0x1224 or 0x0380; the first two chemistries pointed towards a LiMnO4/LMO cathode chemistry which I was somewhat skeptical of, but did not test further.

Using another gauge with a different, programmable Chemistry ID could have led to a straighter SoC curve. This wouldn’t be too difficult to reproduce, as the battery voltage can be fed to the gauge in order to recompute the state of charge. Additionally, the bq27621 has a Terminate Voltage of 3.2 volts (the gauge considers this voltage to be the point in which it reads 0% SoC), which is higher than the battery’s protection voltage of 2.4 volts (granted, there is very little charge difference in this area of the discharge curve).

My test setup was not temperature-controlled; I live in a house without air conditioning and room temperatures can vary from 15 to 35 degrees C (59 to 95 degrees F), depending on the season. However, I doubt that this would have had too much impact on discharge rate, and this would better represent real-life scenarios where a constant temperature may not necessarily be guaranteed.

Finally, this test was performed on a new, uncycled battery. I suspect the discharge rate would be significantly higher on an aged battery that was subject to a lot of charge cycles and day-to-day wear.

Conclusion

This was the longest-running experiment I’ve ever conducted on this blog. The Kentli PH5’s self-discharge rate lasts longer than a standard Ni-MH battery, but a LSD (low-self-discharge) Ni-MH battery would still last longer, albeit with a lower terminal voltage. The battery, when new, should be expected to last almost 3 years without a charge (although there won’t be any charge left by then); it will hold about 60% of its capacity after 1 year of storage.

To download a copy of the self-discharge test data, click here.